Law or Grace? (4:5)

The location of Jacob's well is very significant spiritually. It speaks of our destiny - blessing or curse, heaven or hell - being determined by God's Law. But Jacob's well speaks of God's grace.

10/10/20235 min read

Samaria is an area between Judea and Galilee - near the northern edge of what is presently referred to as ‘The West Bank’. It took its name from its chief city, which is is about thirty miles north of Jerusalem. Originally called Shechem, it was the town where Abram had built his first altar after arriving in the Promised Land (Gen 12:6–7). Years later, when Jacob returned from living with Laban, he bought a patch of ground from Hamor, Shechem’s founding father; and he too erected an altar there (Gen 33:18-20). But when one of Hamor’s sons raped their sister Dinah, Jacob's sons slaughtered all the Shechemites, presumably taking their land in the process.

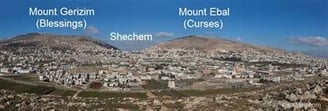

Jacob gifted Joseph a specific plot of land there, above and beyond what he was to bequeath by faith to Joseph’s siblings (Gen 48:22). Joseph was later buried there, after his bones had been brought back to Israel during the Exodus (Josh 24:32). His tomb still exists, only a few hundred yards from Jacob's well. Jacob, perhaps remembering his father’s conflicts with the Philistines over water rights, had dug his own well. It exists to this day, and must have been an astonishing feat at the time - for it is still over a hundred feet deep. But it was reliable and prolific enough to supply water for his whole tribe and their large herds of livestock. The well lay below Mount Ebal, whereas Joseph's tomb was nearer Mount Gerizim.

Shechem lay in a natural amphitheatre between two hills, Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim (Jdg 9:6–7). Earlier, Israel had renewed their covenant with God there, after their victories at Jericho and Ai (Josh 8:30-35). The ceremony involved half the tribes speaking blessings from Mount Gerizim, and then the other tribes pronouncing curses from Mount Ebal. So its geography spoke of a life lived between blessing and curse, between life and death, between heaven and hell. What decided the outcome, would be whether Israel stayed obedient to Yahweh's Law, given through Moses.

After Solomon’s death and the division of his kingdom in two, Samaria became the capital city of the northern part; but underwent frequent changes of dynasty, due to its kings’ idolatry. The curses pronounced from Mount Ebal came into play. Eventually it was invaded by Assyria and ethnically cleansed, its people being replaced by immigrants from other parts of the Assyrian Empire. They brought with them worship of their own gods; but soon blended this with worship of Yahweh - whom they saw as a local territorial spirit.

Later, the Southern Kingdom was also taken into captivity, this time by Babylon: but the exiles were allowed to return seventy years later. They began rebuilding their temple in Jerusalem, under the leadership of Nehemiah and Ezra and with encouraging prophecies from Haggai and Zechariah. But Nehemiah was adamant about racial purity, and wouldn't allow Sanballat (a Samaritan leader, (Neh 2:19-20,4:1-3, 13:1-3) any part in the rebuilding. Sanballat tried to get round this by marrying off one of his daughters to a son of the High Priest; but Nehemiah discovered and drove the young couple away (Neh 13:23-28).

Somewhere around 400 BC the Samaritans built their own, rival Temple - on Mount Gerizim. Excavations have shown it had a massive foundation, very similar to the rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem. Around 320 BC Sanballat's grandson tried the same trick his grandfather had used, marrying his daughter to the jewish High Priest's brother. But the jewish priesthood issued an ultimatum: either the couple must divorce, or the High Priest’s brother would be expelled. He chose the latter and moved to Samaria - where he became High Priest of the Samaritan Temple.

The Samaritans saw themselves as ‘children of Jacob’ and held to the Torah, just as the Jews did; but only the books of Moses, not the historical books or the prophets. They believed Moses was the only true prophet, until another prophet like him arose (Deut 18:15; 34:10). They called this future prophet ‘The Taleb’, meaning the One who would return and restore all things. So their view of Messiah was significantly different than that of the Jews, more focused on His prophetic ministry and not on His nature as Redeemer King.

Their version of the Torah replaced the tenth commandment with one commanding that a Temple be built on Mount Gerizim. They celebrated Passover and the other feasts there, with almost identical ritual to that of the Jews in Jerusalem. Thus from a Jewish point of view, there was a near-exact counterfeit religion, right on their doorstep.

Perhaps some of the rivalry had its roots way back in Jacob's family dynamics. When Reuben slept with his father's concubine Bilhah, he lost his birthright as the firstborn. Simeon and Levi were also disqualified by their ruthless cruelty in avenging Dinah. So Jacob gave the birthright to Joseph, the firstborn son of Rachel rather than Leah. And then, when he adopted Joseph's sons Manasseh and Ephraim as his own, he deliberately crossed his hands and gave Ephraim the firstborn's blessing. Thus Ephraim, not Judah, should technically have had the right to lead the Twelve tribes. After all, hadn't Joseph's dreams foretold his brothers bowing before him? But when Jacob was dying, he gave each of his twelve children a specific blessing. He prophesied that Judah would be the leading tribe, and source of Israel's kings, until Messiah came (Gen 49:8-10). Israel's first king was a Benjaminite (Saul): but David was of the tribe of Judah. This signified God was choosing Judah over Ephraim, and Mount Zion - not Mount Gerizim - as the place of His Presence (Ps 78:67-70).

History moved on, and Babylon was overthrown by the Medes and Persians; then later the Greek Empire became the new 'Great Power' in the region. Its ruler, Antiochus Epiphanes, tried to wipe out Jewish culture, deliberately defiling the Jerusalem Temple. The Jews fought back, reclaiming their own land: in the process, their leader John Hyrcanus completely destroyed the temple on Mount Gerizim in AD 128. Though worship on Mt Gerizim continued, this can only have exacerbated the antipathy between Samaritans and Jews. And then, when Rome took over from Greece, Samaria was classified as part of the province of Judaea which rubbed more salt in the wound.

The intense antipathy meant that Jews from Galilee going up to the Feasts in Jerusalem often faced hostility, from the Samaritans. Though the most direct route lay through Samaria, many preferred to go the long way round, crossing and re-crossing the Jordan in order to avoid the risk of being beaten up en route. Hostility waxed and waned over the years: for example in Jesus’s time, although Jews would not share meals with them, Samaritan food was classified as kosher; but a couple of decades later it was considered unclean.

Today, there are probably only a thousand Samaritans still alive, but they still worship on Mt Gerizim. Having sought to prevent inter-racial marriages for centuries, they are trying to boost their numbers by intermarriage with Jewish women! But in Jesus’s time, there were probably as many Samaritans as Judaeans.

How does all this background play into Jesus's encounter with the woman?

The history, meant she lived under a counterfeit religion of works. The controversy about which religion had 'the truth', was ongoing. And the geography, with Mounts Ebal and Gerizim, spoke of judgement based on one's life and deeds: things in which the Samaritan woman knew she had failed.

The well had sustained Jacob's family through very difficult times. Finding such a prolific water supply, at that depth, had been a major miracle for him. She too had a difficult life, ostracised by her fellow women. But now she was about to experience a greater miracle than Jacob: a permanent supply of living water, entirely by grace!